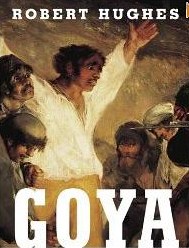

Robert Hughes

Goya

This 2006 beautifully edited paperback bio of the great Spanish painter is a joy and a must-have for art history readers and collectors. Though a paperback, it is a solid one-piece of a a book, with top-quality hard paper and where lots of good-sized paintings are collected throughout. The visual and tact qualities make the book, alone, worth the purchase.

Now the writing. I came across this book after reading Mr. Hughes's previous history of American painting, which left on me such a good impression. I had to look for more from this Australian author. There are two first comments that have to be made: 1 the author writes so well, so fluidly, so devoid of the arrogant academic slang that one has to get hooked on whatever he writes about. The man knows about what he writes, accordingly, he feels no need to take on the act of a typical professor grinding on his subject. And thanks for that. So his story just comes out of himself, it's personal, not anything official, and appropriately so, since few subjects are more relative than art. And 2, the author is opinionated and full of prejudice. That is not good, but not good for the author, of whom I am not concerned in the least; what concerns me are his books, and they are some fine and jolly good ways to spend time and get some knowledge while doing it. On this second point, let's just say that the author lets his books talk as much of himself as of the subject he is dealing with. I find it quite understandable when it comes to arts or politics, because it's all subjective material, no right or wrong analysis, but only a matter of opinion. And I applaud him for his sincerity. His brief statements on all kinds of issues bring out his left-wing political bias but, I believe also, his independent thinking and straightforwardness. He has a thorn in the flesh with religion, though, with Catholicism specifically, and he can't get over it.

The book presents the life and works of Goya. The history of Spain and the life of the artist do not blend, though, Mr. Hughes tries, but cannot make them blend, there's not enough that we know about the man Goya. The author shows very well a lot of works of Goya and uses them to thread the story of his life and times, in a parallel sort of way. The talent is in the author for telling stories that catch the attention of the reader, for picking the bits of life that interested Goya to make his paintings and sketches and which are also the object of our interest. And there's lot of stuff to talk about: Goya painted war scenes, crimes, female bodies, street characters, bullfighting, portraits, monstruous things, violence and stupidity, sanity and insanity, sainthood and evil. Goya poured himself and as much of Spain into his drawings and paintings, and those are our main source of information. The history, concise as can be, of Spain, that Mr. Hughes presents, is not a matter to produce any polemics, though: he sticks to the official history in the text books (mainly he resorts to Raymond Carr material) without deviating much from traditional discourse. Carlos IV wasn't, however, the cuckolded husband that tradition portrays, if we are to believe more recents studies. The Motín de Esquilache is done away with, also, with the usual and simplistic explanation: that it was a matter of dress code that the people of Madrid rebelled against. Well, yes, but that was the scapegoat for the rising, which would never have taken place if the people of Madrid weren't tickled by the nation's high aristocracy which felt their power skipping through their fingers and going into the hands of foreign ministers like Esquilache.

Hughes is too sympathetic with his hero, Goya. He delivers a self-righteous Goya, an alter-ego of Hughes (all leftists are self-righteous, they are god-less saints), a charitable but unbelievable character: “Goya's immense humanity, a range of sympathy, almost literally “co-suffering.” rivaling that of Dickens or Tolstoy”. At times he is at pains to “explain” away Goya's less likeable actions or attitudes, to excuse him for his -in our modern view- wrong sentiments. I would have liked better that Mr. Hughes used his usual straightforward style and accepted the possibility that Goya might not have been such a politically-correct and laudable person, or even that he might have been quite a dislikeable character deep-down, why not? We have no definitive proof that he was one way or the other. After reading this biography one has an inclination to conclude that Goya was indeed a man of his time, a Spaniard of his time, full of contradictions (he hated violence and oppression but liked bull-fighting, hunting...; he styled himself a patriot and an illustrado but well be called an egotist, fan of Mammon and a Collaborator: “he disliked and despised the new king and his opinions. He never said so”. I am sure he was an old grumpy man, with no patience nor time for fools, a simple feature that already wins for him my sympathy. But Hughes takes his “humanity” too far. He wants to make a caring and lovable Goya in the way of Dickens, but what he presents hints more towards a Franco-like Goya. I'm sure Franco was lovable and caring too, only in a different, more typically Spanish/brutish way, not the British way. If we are to assume that he was a typical Spaniard, only a little more “ilustrado” and sensitive in the modern sense of the word, then he was a brute, a lovable brute, perhaps. Hughes is the one who brings Franco into the book a couple of times by the way, with derogative intentions, of course. So this thing about characterizing persons as good or bad by having them match your corresponding political heroes or foes is nothing short of unfair and unrealistic. As unrealistic and unfair as to pinpoint everything evil on individual characters (Hitler, Stalin, Franco...) and clear all responsibilities from the hands of the folks, the pueblo, as though they were sheep astray and misled. If Mr. Hughes is in the business of saying who is nice and who is evil he should be fair and blame the whole nation, for what whould have been of little Franco without the people who supported him for so many years? And what about silly Hitler without all those nice folks congregated at Nuremberg? And he would be right to blame not only Fernando VII, the clergy, the nobles and so all the way to Franco, but the whole nation of Spain, because this country hasn't been a nation of “nice and well-intentioned” folks for a long long time. But Mr. Hughes takes the shortcut, as self-righteous Leftists do, there's more to gain that way.

Another trait of Goya that puts him in the band of Mr. Hughes's dislikeables is his religiosity. “Twentieth century writers, in their desire to emphasize the modernist rebel in Goya, have often made him out to be irreligious, either an agnostic or an enemy of religion. But this is a crude distortion.” Mr. Hughes arranges somehow to still like the character of Goya in spite of all the evidence that, rather, puts the man among those who are more apt to win his derision, religion being a perfect isthmus test for these kind of occasion. He was a Catholic, admits Hughes, but hey, mind you, “a Catholic without priests”. And thus he is saved from Leftists' Hell. Mr. Hughes's personal commentary on Catholicism comes to the fore in its most crude form in these words: “They (the clergy) were as bad as any modern Catholic priests. They praised chastity but groped boys”. In this case Mr. Hughes does generalize, and quite unfairly, because we are talking about actual crimes, not just behavior or cultural traits. I am not a Catholic and completely understand his point and criticism, but I have to say the author is not being fair. A high percentage of the Spanish population was in the clergy, more in fact than today's hordes of civil servants (funcionarios), being that already a huge number. So the people are, actually, the lawful recipient of Mr. Hughes's derision. Funny and ironic how the author's alleged love for Spain is but a covert and general derision of the nation in general.

An interesting historical piece of data that I have found is that 12,000 Liberal Spanish families went into exile when the French invaders had to leave. That's a lot of unorthodox people leaving, from a country already destitute of enlightenment, tolerance, morals, and plagued with envy, laziness, hipocrisy and thievery. No wonder things only got worse thereon. The best have always left or been made to leave; zero tolerance if you differ.

My attention paused at this comment the autor made when comparing nasty Fernando VII to hated Godoy: “At least you could have some admiration for his [Godoy's] sexual potency.” I just had to smile when I read this. I mean, what on earth has sexual potency got to do with the merits or demerits of anybody?

In spite of all the criticisms I have made of this author I strongly recommend his books, and this one in particular. On matters of art I prefer one strongly opinionated person, capable of holding the interest of the reader with stories and acnedotes that are relevant and interesting to the lay reader, than to read from a sulky or petulant fellow who shows off and lives regularly on the subsidy of some elitist institution or government. Lo cortés no quita lo valiente.